Thank you to Eric Asimov of the New York Times for recommending this Cornelissen write-up to readers in the Monday, March 19 edition of “The Diner’s Journal.”

Thank you to the judges of WBC 2012 Wine Blogger Awards for selecting this post as a finalist for The Best Blog Post of the Year category.

***

On Mt. Etna, on the Island of Sicily, Flemish wine maker Frank Cornelissen has made home for his own multi-purpose farm. In developing the property, Cornelissen’s commitment was to respect the constitution and potentials of the land itself. As he describes it, humans tend to assume they can know in advance what nature is capable of, or how to control it, when in actuality humans will never have such vast capacity. By imposing their own assumptions onto nature, humans do damage to their environment, and fail to gain what is possible without such imposition. As such, Cornelissen’s goals are to shift from such perspective and instead interact with the environment he calls home on its terms. To do so, he sees himself as required to intervene as little as possible, and, in an almost psychically open way, read the vineyards needs through careful observation and delicate response.

One of the results of Cornelissen’s choices is the belief that only 95% of his property is actually suitable for vines. The rest he allows to either rest in its own productivity, or he uses to grow other plants and tend various animals.

Cornelissen’s commitments to low intervention extend into his style of wine making as well. As he describes it, only in the 2002 and 2003 vintages was he required to use the addition of sulfur to prevent spoilage due to incredibly wet weather in those years. Otherwise he has succeeded in allowing the wine to make and maintain itself. Other wine makers generally see the use of sulfur as standard practice to keep the wine from moving past the alcoholic fermentation process straight into the development of vinegar (VA). Even biodynamic wine makers take sulfur as an acceptable, and necessary, additive for these purposes. Cornelissen on the other hand takes it that nature will make the wine for him, and additives to either the land or the bottle are best avoided.

The reality of Cornelissen’s bottlings is that VA does play a central role. While one can describe some wines as fruit driven in their characteristics, or others as mineral driven in theirs, I’ll say that Cornelissen’s wines are actually VA driven in their constitution. It would be easy to take such a statement as meaning the wines are undesirable but to do so would be to judge Cornelissen’s wines on a standard that is not necessarily meant for his product. Just as he takes it that the land should be opened to and read on its own terms, it seems Cornelissen has produced something that has to be considered as a kind of self-made unknown. To allow his offering to show what it has to give, Cornelissen’s wines must first be opened to without standard expectations. I want to clarify here that I am not saying Cornelissen would want to describe his wines in such a manner. Nor am I saying that his wines are turned to VA. When stored and transported properly such a result is unnecessary. Even so, his wines consistently carry distinct VA notes that are definitive of his creation. With this in mind it becomes interesting to reconsider the ways in which such a characteristic could be desirable, and when it would have gone too far.

Munjebel 7 Dry White Wine

click on comic to enlarge

Cornelissen’s Munjebel 7 offers a blend of Carricante, Grecanico Dorato, and Coda di Volpe. The wine, interestingly, is a non-vintage blend, meaning Cornellisen creates it from the juice from grapes across multiple years. In this way he is able to pull on the strengths of his vineyard from season to season as needed.

As discussed, he abstains from the addition of any preservative measures in the fermentation or bottling, and has gone without the addition of sulfur in all but two years.

Production of the Munjebel White includes extended skin contact and lack of filtering as well. As a result the wine carries a substantial tannin level for a white (it’s basically an orange wine to be quick about it), and also has a hefty amount of sediment. Matt Kramer of Wine Spectator even went so far as to compare the sediment levels of Cornelissen’s whites to that offered in a snow globe. Without the addition of sulfur the worry is that once standard alcoholic fermentation is complete the wine will continue to turn from alcohol to vinegar (VA). Some notes of VA are common in many wines and can be desirable at a lower level adding another layer of complexity, but it is generally understood that higher levels of VA mean a wine is, well, no longer wine.

Cornelissen’s whites are widely considered his more challenging wines as the flavor combinations are unusual alongside atypical structural components as well. with higher tannin levels and lots of texture. The Munjebel 7 remains consistent with this idea. Though I have adequate experience with orange style wines, and wines with VA notes, this particular one carried more VA than I’d tend to appreciate with less of the flavor elements I tend to look for as well.

Cornelissen’s wines are also generally understood as more volatile than more mainstream (read: with more preservative measures) wines. The VA elements showing in each is indicative of their overall volatility, but more interesting than that is the simple variable nature of each particular wine once opened. It’s typical to notice an interesting wine develop in the glass as you drink it over the course of an evening, but the effect on Cornelissen’s wine is sped up such that in any 15 minute window the flavors and quality change dramatically, with even the density and color in the glass changing noticeably. As such, Cornelissen’s work makes apparent how important it can be to focus in on the ideal drinking window of any wine–how long after being opened it begins to show best and for how long such qualities remain in balance as desirable. In Cornelissen’s case, the ideal drinking period of his wines is shrunk down to incredibly small windows but the experience of hunting that ideal time frame so acutely shows a lens on the same experience with wine more broadly.

It’s typically understood that when drinking a Cornelissen you wait 15 minutes after opening before you taste it due to the funky aromas arising from the bottle, and then you finish that bottle within 2 hours. That is, in the first 15 minutes the more aggressive notes need to ‘blow off’ the bottle, and at the other end, the wine begins to ‘fall apart’ after its been open for two hours. Again, the pace and life span of a wine is shrunk in Cornelissen’s work.

In each of the Cornelissen wines enjoyed with this tasting the 15 minutes–2 hour advice proved true but most especially in the case of the Munjebel 7 white, and the Contadino. In both cases the wines were complete (undrinkable) before the close of the 2 hours, and both peaked at 20 minutes of opening showing a preferred drinking window of 15 minutes from opening until 20 minutes later. After that 20 minute window the flavors became disjointed, increasingly funky (in an unpleasant way) and progressively more putrid. The putrid qualities were most obvious in the white.

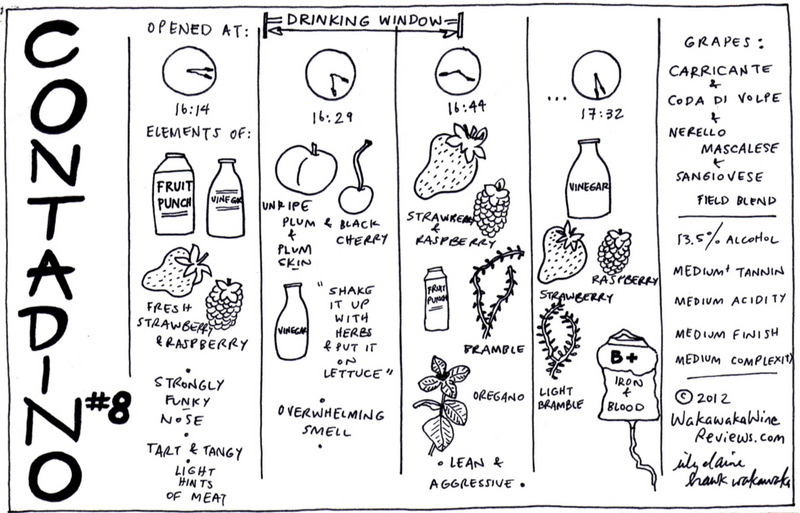

Contadino 8 Dry Red Wine (aka. Rose’)

click on comic to enlarge

The Contadino 8 is considered Cornelissen’s entry level wine both in terms of price and overall drinking accessibility. Within the United States it is also the most commonly available for purchase either in a retail location or at a wine bar.

The Contadino showcases a field blend of both red and white grapes pressed and co-fermented. While it is labelled as a dry red wine the public often calls it Cornelissen’s rose’.

Though the bouquet and aromas on the Contadino were more appealing than in the Munjebel White, the Contadino also lasted less long in the glass and turned to undrinkable more swiftly. That said, this is a compelling, albeit strange, wine. The first time I was lucky enough to drink the Contadino was due to the generosity of Chris at Terroir in San Francisco. It was starkly atypical compared to other wines, and hard to make sense in that first experience. Still, I found myself returning to it in mind repeatedly over the next several days, and even occasionally for months since somehow craving to have it again. It was that experience that led me to purchasing it to taste again this time alongside these two other wines.

Like the Munjebel 7, the Contadino 8 transforms repeatedly in the glass. It shows the same funky nose (undrinkable) when first opened and becomes more approachable after the first 15 minutes. The ideal drinking window stands at 15 minutes from opening till 20 minutes after that initial 15, with characteristics of bright red berries and stone fruit, bramble and herb, VA, and fruit punch showing throughout that time period. After the 20 minute drinking window the wine’s characteristics dramatically change and become infused with elements that lead to people calling it by its cult name–Unicorn’s Blood.

My understanding of the nickname at first was linked to the intense fanaticism people get for this wine–I’ve even read reviews where people claim they were so strunk by the Contadino they don’t want other wine since. The devotion of Frank’s fans is certainly part of it, but if you wait till the one hour mark you find out the other reason–the wine begins to smell clearly of iron oxide and in the mouth it actually tastes bloody.

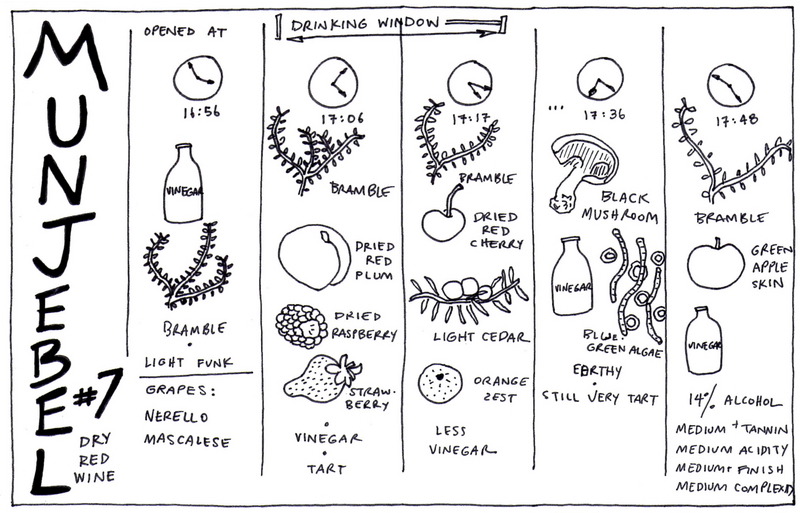

Munjebel 7 Dry Red Wine

click on comic to enlarge

The red wines of Frank Cornelissen are consistenly his most approachable, especially those focusing entirely on the Nerello Mascalese grape. The Munjebel 7 Red offers higher tannin levels, which not only help keep the wine from developing as much VA but also offer the structure necessary to balance the present VA notes. The Munjebel 7 Red carried the least VA overall, as well as the highest tannin, and while still quite a tart wine it was generally less so than the other two, and also than the other Cornelissen wines I’ve tasted previously.

If you’re looking for the Cornelissen experience, his Munjebel 7 Red is my first recommendation. It’s still strange but the most approachable and offers the best balance of intrigue, interest, and drinkability at the same time. That isn’t to say it drinks like a typical red. It is simply the most balanced of these three mentioned.

Again, the Munjebel 7 Red needs to sit open for 15 minutes before drinking and then does best drunk soon after but the drinking window extends for 30 minutes after the intial 15 minute wait. The red lasts longest after opening, though still begins to disintegrate, becoming disjointed and VA ridden a little after the 2 hour mark.

The flavors here were pleasing within that ideal drinking window, showing red stone fruit and dried berries, earth elements, and bramble. After, it became progressively tart and even showed the overwhelming nose of an algae bloom as it sat open longer.

***

If you are interested in tasting Cornelissen wines for yourself, I strongly recommend sticking to one bottle opening in a sitting. Side by side, the Cornelissen portfolio compounds on itself with the VA becoming overwhelming, and the effect in the mouth even showing as uncomfortable. I have seen people do small pour tastings of multiple Cornelissen wines with some success but even there the flavors are so tart and VA driven I believe the wines begin to erase from your palate the individuality and appreciation of each. It is best to taste one of these wines on its own to give it its due.

Cornelissen’s wines are such that many people simply will not like them. Their strangeness at the same time has produced a rampant cult dedication with people strongly seeking these wines out, and others swearing by them. Still, they also show their own divisive power with people carrying strong reactions either for or against them. Many also claim Cornelissen is simply crazy because of what they take to be his extreme wine making practices.

Crazy, in my mind, seems a misapplied notion. There is a consistency to Cornelissen’s farming and wine making practices that is admirable, even if my preference is to have his wines with less frequency. The dedication he has to his land, and to his overall project is both fascinating and honest. To believe that one of the products of his work–these wines–should be judged simply on the standards of more mainstream wines is a mistake. They carry standards of their own–miniaturized drinking windows, delicacy of flavors married with aggressive structural elements, fragility of transport, and, when those self-given standards are respected, beautiful insight into an alternative recognition of treasure.

Copyright 2012 all rights reserved. When sharing or forwarding, please attribute to WakawakaWineReviews.com

Well put! I feel like I finally understand those wines. Lovely balancing act. Cheers!

I really enjoyed the “drinking window” approach that you took with your drawings for this review.

Matt Kramer’s “snow globe” comment was pretty funny.

Cool article on these wines, I agree that they’re a bit of a trip to taste. My first experience with the Contadino #8 was at at tasting with some fellow wine geeks and someone handed me a glass, saying; “here try this” and chuckled as my nose wrinkled in a combination of disgust and bafflement.

I think though, in the interests of accuracy, you might have mentioned that the “vinegar” aspect of VA-tainted wines is only part of the story. Volatile acidity can be caused by many different bacterium and yeasts in the wine, and there are multiple instances where those organisms can begin their nefarious work. The idea of letting nature express itself is one I think a lot of winemakers strive for, but to deliberately not care that your wines are starting to get full of nasty things like VA could be construed as irresponsible..That said, my detection threshold is quite low and therefore I struggle with a lot of the “natural wines” or “minimal-intervention” wines out there due to their excessive VA (and often, Brettanomyces) levels.

Two articles I reference are:

http://www.winebusiness.com/wbm/?go=getArticle&dataId=49280

and

http://www.winebusiness.com/wbm/?go=getArticle&dataId=54424

Cheers! 🙂

Thanks for your comment! You offer great information that is nice to clarify here in the comment section rather than overwhelm the original post with even more information.

I appreciate your comment too about there being other ways to “let nature do its work.” It’s true–a lot of wine makers strive for such an approach with the understanding that there are certain practices that stand as appropriate interventions to keep the wine from turning. Sulfur being an easy example.

Thanks for the references too! Happy to see your comment and its contribution to this sort of discussion. Cheers!

These wines sound really interesting and really challenging. The VA part is actually less off-putting to me, at first blush, than the description of Contadino #8 as tasting like blood. Something that is very welcome in a steak is very unwelcome in my glass! (Not that I’ve ever had Unicorn steak, to be clear)

I think it’s really enlightening that the drinking windows turned out to be quite short for these wines. Not wines to linger over and allow to blossom in the glass, at least after the first 15 minutes! Did the change in temperature contribute to this? I am curious about the best serving temp for these wines – I’m imagining maybe a touch cooler, like cellar temp for the reds. Thoughts?

Cornelissen makes clear his wines need to be kept at below 60’F both for storing and serving. They definitely change as they get warmer and will turn in the bottle if you store them above 60 too.

[…] post “What We’re Reading” and Asimov gave a nod to Hawk Wakawaka Wine Reviews post entitled Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine’s Natural Drinking Window via Munjebel 7 White & …. I hope you will take the time to open the link and check out this post and others by Lily-Elaine […]

[…] article: Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine's Natural Drinking … 6277 Thanks! An error occurred! argentina, australia, california, chile, […]

[…] Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine’s Natural Drinking Window via Munjebel 7 White &… […]

[…] Lily-Elaine Hawk’s “Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine’s Natural Drinking Window via Munjebel 7 White & …“ […]

Good work… My article on Cornelissen is at http://www.winebehindthelabel.com/frank.html

Good luck with the award.

SDG

Congratulations on the well- deserved nomination!

Hi Jameson, Congratulations to you too! I didn’t find your comment until tonight. You do wonderful work on your blog. I’m grateful too for having gotten some time with you in Portland.

[…] Lily-Elaine Hawk’s “Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine’s Natural Drinking Window via Munjebel 7 White &am… […]

[…] Another pleasant surprise is Lily-Elaine Hawk’s Hawk Wakawaka Wine Reviews for best new wine Blohg and also another nomination for Best Blog Post of the Year with “Thinking Frank Cornelissen: Considering Wine’s Natural Drinking Window via Munjebel 7 White & …“ […]

[…] Jim Bud’s “Pancho Campo resigns his MW“ Lily-Elaine Hawk’s “Thinking Frank Cornelissen” Meg Houston Maker’s “You Just Opened a What? Cooking Tips to Make Food More […]

Ok, I have to say that I loved your drawings. Not only they were informative, well done but they were whimsically funny, speciaily the Iron Blood drawing. I loved it! Tin! Tin!

Thanks so much, Claudia! Really nice to know you enjoyed!

Please put me on your mailing list

Hi Colin, you can sign-up by putting your email in the subscription window on the top right of the website. Thanks!

[…] Standard clearance list in 1.5L format for $88. Who could pass that up? I am perplexed by Cornelissen’s wines after blind tasting eight of them last year. The wines seemed to beg for food, and as so many […]