***

Post edit:

4 January 1960 Camus died in a car accident with his publisher and dear friend, Michel Gallimard. Camus was only 46.

***

My Underlying Views About Giving Wine Its Due

My commitment, both in terms of wine, and, to be honest, generally, even with people, is to strike a balance resting on open minded with standards. When it comes to wine, in striving for this balance I push myself to imagine my way into a glass–to ask what conditions would it be desired under, and who would want this wine when? even when I am not thoroughly compelled by the particular wine myself. My purposes in taking this approach are to push myself to understand wine better by pushing beyond my own immediate matters of taste. But these purposes come to a close when it is time to consider points like the production quality of the wine–how well the flavors balance, if the structure holds together, if additives or interventions have done damage to the flavors, or if maybe the original cuvee was simply never up to par. That is, I am open minded, and I want to learn what wines from different regions or grape types have to offer even if I haven’t tended to like particular regions or grape types, but I also recognize this is not a world of wild relativism. Some wine really is better than others, and damn it we all know that to be true, even if some of us might try to blindly on occasion pretend otherwise.

I imagine the world of wine as an expression of someone’s life–both in terms of a wine maker having spent time to make it, but also in terms of some wine drinkers wanting to take time to taste it. But the truth is, the with-standards part of the situation means there is a limit to any imagining; we can’t pretend there is better quality to a wine than is there. Let me be clear though–I believe there is a difference between quality standards as in, the production and growing conditions that imprint themselves into a wine, versus standards of taste that arise out of my own training, life, and experience. The first I am going to demand myself to recognize and hold regard for, the second I might only partially be able to help. I can push to learn my way into a new wine or wine style–and any of us have done this at least a little bit if we’ve gotten far enough to know the name of more than a handful of wines (the matter of taste)–and I can also learn how to better recognize when a wine is poor quality, and whether it’s because the grapes didn’t ripen well, or the wine maker interfered too much during production (the matter of quality).

A Very Small Fervor in Wine Blogs: A Rants About the Quality of Wine Writing in the Wine Blogging World

As 2011 drew to a close a very-small fervor occurred on wine blogs. Let me say again, very small. However, it’s a fervor worth considering. At least two wine bloggers took their end of year, or first of year moment to rant about the poor quality of wine writing to be found in wine blogs. In a certain sense I take it this is no profound claim really. The idea that there is a glut of work done in this area (wine) is in no way unique; the idea that this work being done on wine itself is often not very creative or sophisticated, is also not peculiar to this one field alone. The internet drowns us all in mediocre production. So, in as much as either of these wine bloggers simply wanted to complain, well, way to contribute to the drowning. I’m willing to assume, however, both wine bloggers (who will be named shortly) hoped to do more than just that. In other words, there is good reason, it seems, to consider some of their points raised.

On January 2, The Passionate Foodie posted what he called a rant and a “call you [wine bloggers] out once again” demanding that “There is not a single wine blog out there that cannot be improved” (italics original to The Passionate Foodie’s own statement, not my emphasis). As @dfredman so aptly responded via twitter, “Is there _anything_ that can’t be improved?” I take it the implication of @dfredman’s response is that there is nothing profound in claiming that any wine blog could be improved. That, if that is the only assertion being made, it is too obvious. It is simply true of anything. There are times, however, when the obvious must be pointed out, of course; or, when something only becomes obvious after it is said. The truth is, there is a glut of wine writing on the internet these days, and I take it The Passionate Foodie (PF) was placing a sort of call to attention to anyone doing such work–challenge yourself to always improve or, get the hell out. That is, be better, or why bother? In as much as this was his point, I agree. I want to point out too that PF makes a point of stating he expects this challenge of himself as well. With that being the case his point becomes less of a rant, and more especially worth considering.

The second blogger, who I’ll mention and name more specifically later, raises a different kind of concern, however. In his post, some of the ire expressed is about what even makes it worth reading wine blogs at all, and his challenge pushes more on a demand for wine writers to explain to him why they even bother to write what they do. As will be explained a little further on, he gives specific issues in which he thinks many wine bloggers fail. In response to any such rant certain standards, I think, must be met by the person doing the ranting for them to escape the trenches of their own criticism. As just said, in as much as someone offers mere complaining, it seems they are only contributing to the glut without actually doing much to transform it–they are encouraging the drowning in mediocrity while tricking themselves into thinking they’re speaking against it. In other words, without offering either insightful standards for the apparently poor blog producers to reach towards, or information to encourage the possibility of insight and education, then no real work has been done. Criticism is not necessarily productive critique, to put it another way. To be clear, I offer this claim more for the sake of the general point, and less for the sake of calling any specific person out. I take it readers can decide for themselves, if they wish, whether material they read online fits such a description.

In considering the conjunction between PF’s challenge, and the name of his own blog–passionate–I can’t help but consider that the answer to escaping mediocrity, and improving our own blogging standards rests precisely there. In our own passion.

Considering the Question Why Bother?

What, then, does it mean to live the passionate life in relation to wine? Camus delivers an answer, I believe, through his interpretation of the Ancient Greek tragedy of Sisyphus.

(a) The Story of Sisyphus

As the story goes, Sisyphus was a tricky, spoiled little bastard used to getting his way. As first, the son of a king, and then king himself, he’d come to rely on his own powers of persuasion to get desire fulfilled imminently and consistently. Sisyphus got what he wanted when he wanted it. With such charisma, Sisyphus successfully went on to trick even a series of gods and goddesses out of his own mortality, and just desserts, all towards the purposes of his own pleasure. In this way, Sisyphus over extended his powers of persuasion to gain advantage over his own natural place below the gods, the natural rulers of the cosmos, as well. (Details of exactly how Sisyphus did so can be found through a simple wikipedia search if you’re so unfortunate as to not know the story already–really, Ancient Greek tragedy is one of the most insightful, and interesting sources of human drama and ethical instruction, though admittedly interpretive work must be done to gain the later).

Finally, as a result of Sisyphus’s arrogance the god’s enact an ultimate punishment. He is forced to roll a boulder almost too great for his own strength up to the top of a hill for all eternity. Each time the boulder reaches the crest of the hill it will pause only briefly and then roll to the bottom again. Sisyphus then must turn and follow walking full aware of the fate that awaits him–to roll the boulder up to the top again and again for all eternity. As written, this situation will continue without hope or recourse for change. There is no way out. (In case it wasn’t obvious already, right this minute as you read and I type this Sisyphus is down there rolling, then following the boulder even now.) Futility, then, would seem to be his punishment: the burden of a rock almost too great to push (with no hope of increased strength since this man is, after all, dead). Here Camus steps in and tells us that the lesson of such a story is twofold. First of all, Sisyphus’s situation is our own–we each push our own boulder in futility to the top of the mount again and again only to watch it pause briefly and collapse back then to the bottom, with no choice but to follow and push it up again. Secondly, we must assume Sisyphus to be happy. Yes, happy. We’ll get to that point in a minute.

(b) Ways We Resist the Truth: Complaining About the Negative; Refusing to Do the Work to Understand

The last four years I taught Camus’s Myth of Sisyphus to University students (my own boulder to push) and consistently what I found was that the first most obvious response to Camus’s ideas was a great tripitaka of resistance, dislike, and disagreement. When pushed as to why people either disagreed with or disliked Camus’s ideas about the futility of our life situation, they consistently responded that they didn’t like Camus because he was negative, and they disagreed with him because they didn’t think our lives could only be as negative as they took Camus to be.

I recognize that all of this must read as some weirdly evasive response to The Passionate Foodies challenge, or, perhaps as so evasive as to be no response at all. But, I will say to you that it is not. I really am getting somewhere with all of this, but considering these sorts of ideas takes time, and I am a god damn philosopher, after all. I will give away the punch lines, however, and tell you this–where I really am getting is to two points. One, if we’re going to understand what it means to rise to an occasion and challenge ourselves to be better, then we need to bother to understand what passionate living is really about and Camus is one clear path to understanding that. Two, it is possible to genuinely disagree with or dislike something only after you have actually done the work to understand it, and so to see how Camus will help us in our very small fervor we have to do the work of understanding Camus. Short of that, if claiming to disagree with something you haven’t actually grasped, then you are running on the fumes of arrogance, and as anyone that has driven a car long enough understands–fumes run out and the engine quits.

So, we’re going to have to get back to striving towards an understanding of Camus before we can decide if we disagree with or dislike him, but we’re also going to have to consider why the fuck he’s even relevant here. Obviously. Let me point out though that some of the reason I bring up Camus is actually because of the second blog post contributing to this so-called very small fervor on wine writing–Evil, of Evil Bottle: The Dark Side of Wine, posted “The Wine Blogger Dilemma” in which he calls out wine bloggers for their mediocre efforts at taking a stand, expressing their more genuine interests, and choosing to commit to a style of wine they do or don’t like so that they can recommend with some consistency. He also calls wine bloggers out for trying too hard to cave to big brother wine magazine by doing things like award points, and establish or use rating systems that just repeat what the magazines are already doing. The implication is: why blog if you’re just trying to be a magazine?

I take it part of the point of either Evil, or PF’s rants is to say–why should we read your crap? I want to read something interesting. If you’re mediocre and just repeating what everyone else is doing, then you’re certainly not giving me interesting. Here is where we come back around to Camus.

An Elongated Lead-In to Answering the Question Why Bother?: Camus and the Passionate Life

(a) We Feel Our Lives are Meaningless

Again, Camus emphasizes that each of us are living a life of pushing a boulder just to see it roll down again to the bottom. That is, in the grand scheme of things our lives are essentially meaningless–we’re going to die and be forgotten no matter what we do here. Any of us, even those of us that hold on to a story of afterlife or god(s) caring for what we do, have felt that reality. There are too many lyrics, or stories, or poems, or movies emphasizing that feeling for you to deny it. Even those that demand they are living in faith have to admit that your faith only gains relevance in the face of comprehending that fear and feeling of meaninglessness–in fact, it is precisely because we feel our lives are meaningless that living in faith gains any significance at all. If you had actual without doubt proven certainty of something like an afterlife or god(s) your claims of faith would be irrelevant. Faith is, by definition, conviction in the face of doubt. (Let me be clear: I am not in any way arguing against spiritual convictions here. I am instead pointing out the structural context in which they operate. In a sense you could take it i am actually giving greater credence to spiritual conviction by pointing out how very real the challenges of holding them are.)

It is in this point about the apparent grand-scheme meaninglessness of our lives that people get caught in an interpretation of Camus as negative. But when a reader does that they are failing to grasp Camus at all, and stopping before they’ve even started doing the work. It is precisely because we feel our lives as meaningless that Camus says our lives can begin to have genuine meaning. To understand this point, however, we must first consider another feeling we cannot help but have.

(b) We Feel Our Lives Are Meaningful

We cannot help but feel our lives are meaningful at exactly the same moment that we are convicted they are not. Camus points out that many people respond to only one of these feelings and cave to nihilism–a view that nothing they do matters–or to zealotry–the view that everything they do matters for a very particular reason external to themselves. Camus brings this point up to demand that both approaches are disingenuous. They are a kind of lie against the reality of human experience. Instead, the only truth we can hold with actual certainty is that we experience both feelings mentioned as true–we really do feel that our lives do not matter in the big scheme of things, we really will be forgotten no matter what we might happen to accomplish in our lives; and we can’t help but care how any little thing we decide to do happens to go too.

If you don’t believe me on the first point about meaninglessness, see the statements I’ve already made about faith all over again and spend some more time thinking on them.

If you don’t believe me on the last point that you can’t help but care about how things you participate in go, then consider almost any straightforward, everyday moment where you get frustrated that you’re running late, that traffic is backed up, that you might not find that dinner ingredient you are looking for, etc. Then consider how often we respond to larger moments too. We’re irritated about the current people available to vote for, for political office; we are upset our sports team lost the game (even if just a little bit); we worry if we’ve made the right decision about taking a job, leaving a job, asking for a raise, etc. We can’t help but invest in activities we care about, and we do it all the time.

(c) Our Lives Feel Both Meaningful and Meaningless

Here is the important part though–Camus demands, again, that the only thing that we can hold onto as true is that both feelings are part of human experience (we feel both as humans), and the two feelings are simply irreconcilable. There is no honest way to reduce one of the feelings to the other, or to negate either. As long as we are living a human life we will experience both as true, and live in the tension of them pulling against each other. To live a human life is to live a life defined by a conflict of meaning. We experience affects like despair, or even neuroses over whether we’ve done a good job, precisely at the crux of where our feelings of meaninglessness and meaningfulness intersect. That is, it is because of the conflict of these that we struggle for how we will judge our own actions. It is the tension of the two that informs so much of how we experience our own lives.

More detail on that point will have to wait for another occasion. This is supposed to be a post about wine, after all. Dear Jesus, let’s get on with it.

Camus shows us that the paradox I just described is actually an incredible blessing, and that if you truly understand the import of the Camusian paradox then upon reflection of the burden of the boulder you have to recognize that Sisyphus is happy. Here’s how.

(d) Sisyphus is Happy

The burden of the boulder belongs to Sisyphus alone. And, in fact, without them realizing it, Sisyphus tricked the gods again. They gave him a gift they didn’t know he was getting. In the moments that Sisyphus is pushing the boulder the situation demands almost the entirety of his strength. The rock is so heavy (I like to call it the mo-fo boulder it is so big) that all of what Sisyphus is must go into pushing it–that is, it is almost beyond the limits of his strength to move that rock. Any of us that have pursued activities that hard know when you are doing something almost beyond your limits you don’t have time to reflect thoroughly on what you are doing, you just have to do it. So, it really is the case that almost all of what Sisyphus is must be directed at pushing that rock–it takes almost the entirety of his strength, and certainly all of his concentration. When he is pushing the rock, he knows nothing. He is not reflecting on his situation at all. That is, he has no time to be self-conscious about what he is doing because he is too busy doing it. All he is is pushing the rock. So, strangely enough (and here is the first half of the gods’ gift) in the very moment that looks to us as Sisyphus’s burden–pushing the mo-fo rock–he is actually receiving a break from his (after) life circumstance. He is too completely involved in what he is doing to be perturbed by it.

Here’s the second half of the gift–when the rock pauses and rolls back down again, Sisyphus cannot push anymore. The rock is, in a sense, no longer his. He has given it away to its fate of cascading to the base of the climb. It is in this portion of the challenge that Sisyphus receives his other rest. He no longer has a burden. Here he can choose not what he has to do (he will walk down the incline after all), but how he wants to be. It is only here that he is fully conscious, and it is in that moment of having completed his task, and so then given it away to follow its own fate, that Sisyphus is fully awake in his own existence. He faces his fate with certainty–he will push the boulder again–while dwelling in the full aftermath of his own accomplishment. He did successfully push the boulder almost too great for his strength. And now he gets to choose how he wants to experience his fate, and thus choose what it means to him. According to Camus, because we know Sisyphus is fully invested in and aware with clarity of his task of life with the boulder, both up and back down the hill, we must assume him to be happy. It is that combination of full investment and awareness that offers the possibility for a happy life. And it is this combination that is the ground of the passionate life as well.

The Answer to The Question Why Bother?: What It Means to Live the Passionate Life, aka., The Same Answer as What It Means to Challenge Ourselves to Do Better in Wine Blogging

Camus illustrates how a passionate life is one we recognize as fully our own. It is only ourselves that pushes the rock, and only ourselves that releases it to the world to roll where it will after we have brought it to its fruition at the top. If we’re looking too heavily to standards outside ourselves to imitate (like wine magazines), and then blaming anyone but ourselves for the results of mediocrity-by-imitation instead of innovation, we’re failing to recognize our own responsibility for our work. Or, if we’re writing complaining rants against writing that bores us without seeing that our boredom is our own problem–let’s look to what keeps us interested–on the one hand; or, on the other, without offering any footholds or handholds that help garner greater knowledge for others, or possible standards to strive for, then we’re failing to help produce the world we claim we want to live in. We’re just contributing to the drowning. This responsibility for our own lives, and creating the lives we want to live, is true whether our rock is getting the kids up every day for school, or, teaching Camus again for a new round of college students (I gave this college students rock away, though apparently without giving the Camus rock away), or, if it is in choosing to continuously strive to write better wine blog posts. It is only us that pushes the responsibility of that choice, and once the task has reached its fruition we must give it away to find its own fate. Short of that we are failing to recognize both the way in which we generate the profound meaning of our own individual lives, and the limited control we have on the effect of that generative activity.

It turns out when PF and Evil released their very small fervor at the top of the hill they didn’t get to determine where it would afterwards roll. One place it rolled was here–a very long post dedicated absolutely to thinking about what it means to challenge ourselves to write better about wine, but that I am sure for some looks to be mostly about some damned French philosopher.

For the Passionate Foodie, and The Evil Bottle, A Return Challenge

To PF and Evil, this is my challenge back–I absolutely want to read better wine writing, and I want to read it too from both of you. If you’re to take passionate living vis-a-vis Camus seriously here is what that would mean–writing that is almost more than the strength of your ability to produce–be it in expressing wine knowledge, or stylistic expression, or, in regards to pushing yourself harder to understand wines your tastes might not recognize and relish at first smell-and-sip; or, even better, taking up all three. A post in which you try to do something as challenging as you have ever done, every time you sit down to write. Writing almost more than your capacity to produce, but, importantly, not actually more. Just writing so challenging that every time you release it to the world you have to walk back towards the next post happy.

***

The Acknowledgement

Something I appreciate about The Passionate Foodie and The Evil Bottle is this–both put interesting challenges to themselves in their blog writing and their approach to wine recently.

The Passionate Foodie wrote his post mentioned above as a recap or book-end to the post he wrote a year ago as an original rant+challenge at the start of 2011 for wine writers to “change and improve” their wine blog writing. In his recent post he states that he believes he met his own challenge in the past year by taking more risks, covering more unusual wines, and focusing more on features than on individual reviews. PF’s blog is well established, and his writing done for other publications as well. It’s certainly respectable (p.s. he also writes about cheeeeeessseee. who doesn’t want to read about good cheese so that they can then eat cheeeeeesssseee?). Especially because at the same time he sends out a call to attention for wine bloggers, he also intends to put the challenge to himself to improve further again with this new year of 2012.

Evil Bottle is taking up a more specific challenge this year. On his first post with the new calendar, Evil states he is choosing to expand and deepen his knowledge of American wine. His interests and experience have in the past revolved more thoroughly around European wine, specifically French, and as he said, he intends this year to prove his views of American wine wrong. As he puts it, he is trying to face his own critique of boring wine blogs by generating more engaging material.

The thing about any resolution is that they have to be followed through on before they mean anything. I look forward to the developments from both PF and Evil (as well as many others) in this new year, and to reading along to see how they strive to meet their own challenges.

Cheers!

***

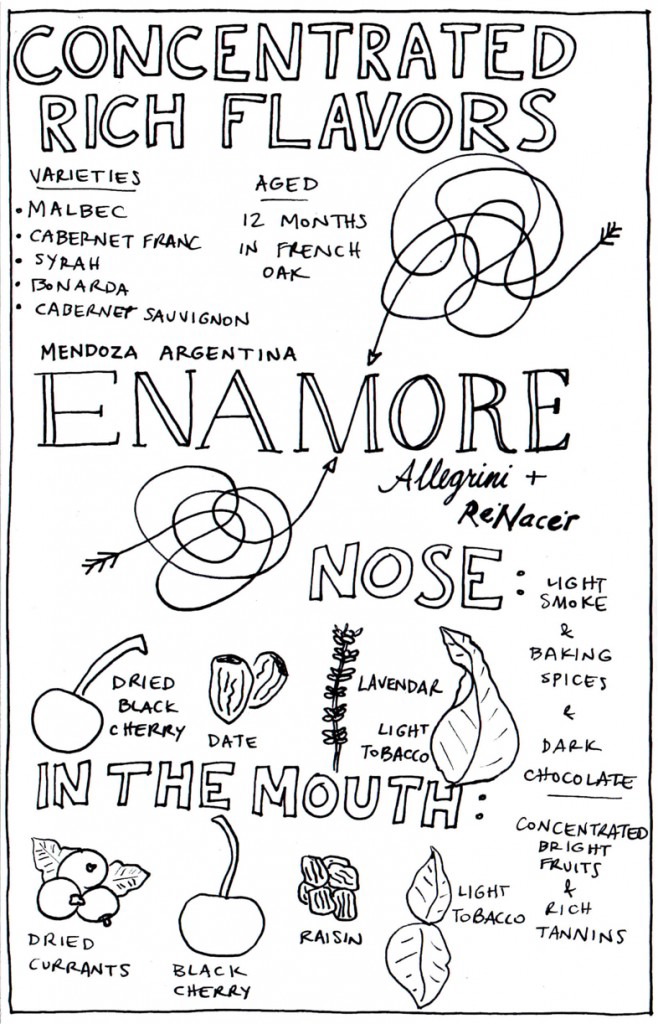

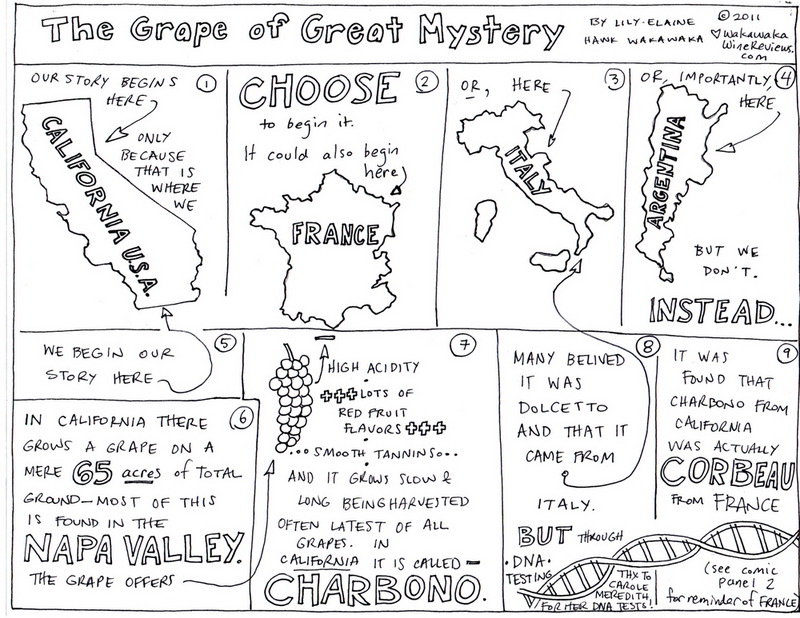

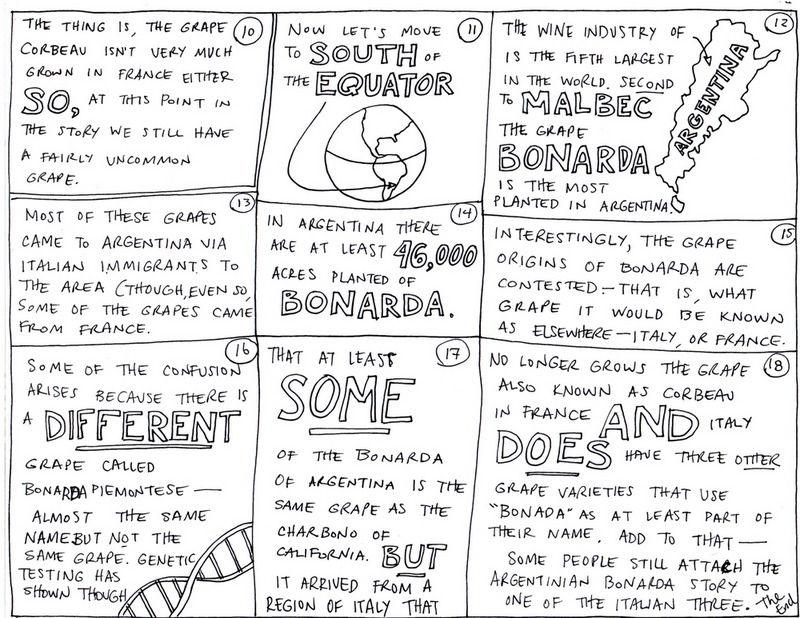

Friday into next week the posts here will be a series of features investigating varietals and their range as shown through differing climate and growing region. You’ve seen me do this work before, but it’ll happen this time in groupings rather than individual reviews, as you’ve seen happening recently. As usual, these considerations of grape variety will culminate in a (color) characteristics card.

I hope you enjoy the rest of your week of om-nom-nom!

(p.s. I promise, in the midst of the reviews these next few weeks, Camus won’t make a peep.)

Copyright 2011 all rights reserved. When sharing or forwarding, please attribute to WakawakaWineReviews.com